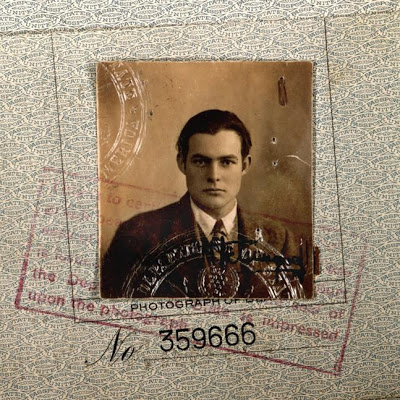

Hemingway era bipolar

A TALK WITH DOS PASSOS REVISITED (1969)

by RONALD PAYNE

(Editor’s Note: The author of the following article interviewed John Dos Passos at his home in Westmoreland County, Virginia, in 1969. Dos Passos, a close friend of Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald, was the author of “U.S.A.” and one of the world’s greatest writers.)

A shy and gentle man, perhaps, best known for his

trilogy, “U.S.A.”, Dos Passos talked freely to me about how it felt to be a

member of the famous ‘lost generation.’

It was a cool and sunny afternoon and Dos Passos

looked out over Sandy Point, talking more about past friends rather than his

work.

He said of the man known as ‘Papa,’ “In the beginning,

Ernest Hemingway was great fun. But he was always a very strange man and had to

prove things to himself as well as to others. In his last years he

was psychopathic (diagnosed with ‘manic depression,’ now called ‘bipolar

disorder’) and had a very bad persecution complex.”

In an interview Dos Passos gave ‘The Washington Post,’

he said that “The Sun Also Rises” was not quite as it should have been. “The

truth never seemed quite the way Ernest wrote it,” he said. “Ernest may have

seen things differently than I. I enjoyed his early short stories very much.

‘In Our Time’ was a very good book. But the novel I liked best of his was ‘A

Farewell to Arms.’ That seems a better account of how things were during the

First World War.”

Of ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls,’ he said: “Some parts of

it were very good, but the sleeping bag scenes between Maria and Robert Jordan

were really over done—a Hemingway fantasy.”

Dos Passos listened intently and, when he spoke, often

talked in quick enthusiastic spurts, awaiting eagerly the next question. He

lost an eye in a horrific car crash that killed his first wife, Katy–and his

remaining good eye is near sighted. His wire frame glasses and round lenses

give him a ‘wise old owl’ expression when he is listening or reaching for

depths of an important answer, usually with an expensive cigar in his hand or a

glass of fine bourbon. He dressed casually and looked the part of the Virginia

country squire.

Asked about the age differences of Hemingway’s wives,

Dos Passos smiled. “Yes,” he said. “Ernest’s first wife, Hadley Richardson, was

a little older, and she was very pleasant. There was a seven year age

difference. And, his second wife, Pauline–also seven years his senior– was also

very nice. But I wasn’t too fond of Martha Gellhorn, his third wife, whom he

dedicated ‘For Whom the Bell Tolls.’ She was ten years younger, talented and

ambitious. Ernest left Pauline for Martha, which was a serious mistake. Martha

was blonde and beautiful. She came to Key West from St. Louis, just to find

Ernest, who was already famous. Mary Welsh, his widow, is a very interesting

person and has protected his reputation, his manuscripts and his legacy.”

Dos Passos sipped his bourbon. “My feelings on

Gellhorn are that she competed with Ernest in a negative way–as a writer and

journalist–competed with him in covering the 2nd World War. Gellhorn, was of

course, could do nothing to raise Ernest’s stature as a literary figure, but he

certainly helped and boosted her career with his publisher, ‘Charles Scribner.’

Martha Gellhorn was a good reporter and a good novelist, but Hemingway opened

doors for her that she could not possibly have opened for herself, especially

with his editor, ‘Maxwell Perkins,’ who discovered Scott Fitzgerald and Thomas

Wolfe. That cannot be denied. Perkins was the greatest editor in the United

States–and perhaps, the world, at that time. Before his death in 1946, Perkins

had also discovered and nurtured ‘James Jones,’ who went on to complete ‘From

Here to Eternity.’ Martha owed a lot to Ernest for his help in getting her

recognized and established.”

Dos Passos had recently read from his works at

theUniversityofTexas. “That was a couple of years ago,” he said. “But I don’t

generally make public appearances. If you do it for one, you must do it for

all.”

After pouring us both a second bourbon on the rocks,

Dos Passos agreed that that the character ‘George Elbert Warner’ in his novel

‘The Great Days,’ was based on Hemingway. “I’ve used Ernest as a prototype in

many of my stories. Hemingway was a very intriguing and interesting man. He

didn’t like me writing about him, though. He did a caricature of me in one of

his books, ( The character ‘Richard Gordon’ in Hemingway’s “To Have and Have

Not” is based upon Dos Passos), but we had a falling out after I used the

George Elbert character in my novel, ‘Chosen Country.’ Ernest could be very thinned

skin. My first wife, Katy, knew Ernest and his father, Dr. Hemingway, up in

Michigan when Ernest was a boy.”

“Most of what happened to George Elbert Warner in

‘Chosen Country’ really happened. And, it happened to Katy, too. It was her

story, as much as Ernest’s, but Ernest didn’t see it that way, though he used

Katy in a couple of his stories, as well. As a teenager, Ernest was in

love with ‘Katy.’ I’m glad she married me.”

Our conversation was temporarily interrupted as he

received a telephone call from his daughter, Lucy, who was away at ‘Occidental

College’ in California. “Lucy is the joy of my life,” Dos Passos said, speaking

of his only child, born to him and his second wife, Elizabeth Holdridge (Betty)

Dos Passos. “I am very concerned that Lucy gets a good education. The world is

rapidly changing and young people must be made to realize the importance of it.

When my father sent me to Harvard, at the beginning of this century, he not

only wanted me to learn everything I could, but he wanted me to go out there

into the world and use what I had learned. And, he wanted me to forcefully use

it.”

Switching to F. Scott Fitzgerald, the author of ‘The

Great Gatsby,’ Dos Passos said: “ ‘Tender is the Night’ is out of focus.

Scott was brilliant and disciplined in ‘The Great Gatsby,’ but I really must

read ‘Tender is the Night’ again. It strikes me that Scott was overwhelmed with

many of the autobiographical aspects of that book. It is a novel about

psychiatry and his wife, Zelda’s breakdown and confrontation with

schizophrenia. She is called ‘Nicole Diver’ in the story. Fitzgerald often told

me how painful the book was to write. He based ‘Dick Diver,’ who is first

Nicole’s psychiatrist, then her husband, on his own research and feelings about

Zelda.”

Did Fitzgerald really start out writing about Sara and

Gerald Murphy in that novel and end up writing about himself and Zelda?

“Yes, no doubt about it,” Dos Passos said, blowing a

halo of blue smoke from his freshly lit ‘Cubana.’ “The Fitzgeralds were a

handsome couple. Zelda’s novel, ‘Save Me the Waltz,’ was not really a very good

book, cutting into much of the material Scott was preparing for ‘Tender is the

Night.’ She wrote it in six weeks in one of her high manic phases while being

treated in an institution. Scott spent much of his time in Ashville near his

wife, editing out the more embarrassing episodes from their lives from her

manuscript. Scribners sold only about 1,500 copies, but it has recently been

reissued. Zelda’s use of his material incorporated into ‘Tender is the Night’

annoyed him to no end. He spent nine years writing and perfecting ‘Tender is

the Night.’ She wrote about her extra-marital affair with a French aviator,

which almost brought their marriage to a very sudden and abrupt end. Scott forgave

her. He was very loyal to ‘Zelda’ and protected her, always. Her bills for

being institutionalized forced Fitzgerald to move to Hollywood, where he wrote

screenplays for MGM. It was the only way he could survive.”

Was the autobiography, “Beloved Infidel,” written by

movie columnist Sheilah Graham about her love affair with Fitzgerald true?

“Definitely. Everyone could tell that they were in

love who saw them. Scott was drinking badly during this period of his life and

Miss Graham was a great help and comfort to him. I don’t know Miss Graham that

well to tell you much more than that.” Dos Passos switched gears and said: “I

watched the debate, several years ago on television, between my friend William

F. Buckley, Jr. and novelist, Gore Vidal. I have to say I am very much

prejudiced in favor of anything Bill Buckley writes and talks about. Bill, of

course, the conservative editor of ‘National Review’ and Vidal, the liberal

author of the recent bestseller, ‘Washington,D.C.,’ gave us a splendid night of

explosive television. I saw Vidal’s play ‘Visit to a Small Planet’ and found

some of it amusing.”

Dos Passos’s stepson, Christopher Holdridge, had

accompanied us to a paint store in Callao earlier in the day. “Kiffy,” or “The

Kiffer” was now upstairs and Dos Passos quietly shut the door. “I told him

yesterday that getting a job in a sawmill might be a good thing. I don’t know

if he agrees, but when I was a teenager that would have been a writer’s

experience. It would all be an adventure. Something to use in my later

writing.”

Until now–and the afternoon was passing in a hurry–I

felt the interview, while pleasant enough, had been unyielding. I didn’t want

to go home with a story about a great author saying just some ordinary things

that most people already knew. I kept hoping he would say something ‘wildly

unexpected, something exciting,’ as he showed me a photograph of himself with

fellow writers, ‘John Steinbeck’ and ‘William Faulkner’ taken in Japan in 1957.

It came out of nowhere. “It haunts me that Ernest Hemingway

shot himself. After the death–a violent death mind you–of my beloved ‘Katy,’ I

considered doing the same thing myself. My reasons, possibly, would have been

different from Ernest’s, but the result the same.”

Dos Passos, who was usually reticent with strangers,

opened up–only because I asked him about the character ‘Roland Lancaster’ in

his novel, “The Great Days,” a book I very much admired, though it had been

compared unfavorably with Hemingway’s “Across the River and Into the Trees.” It

was sensitive territory, but I pushed on.

” Roland Lancaster, the hero of ‘The Great Days’ is

the most autobiographical character I have ever created. Roland Lancaster’s

life was almost destroyed. He was an author and a war correspondent. Of course,

I was driving the automobile that took my wife’s life. Unequivocally, an

accident, but I was still driving. And, it still killed her. I had the sun in

my eyes. Ran directly into the rear of a parked truck on the highway. Katy was

partially decapitated. I lost an eye–went into shock–into denial. For many

years afterward, I grieved and suffered debilitating bouts of depression that I

never talked about.”

“It is perceptive of you to link Roland Lancaster’s

story and mine together. The abortive trip to Cuba with the girl. Much of it is

true. I wrote that novel to exorcise a lot of painful experiences out of my

soul. My second wife, Betty, really deserves the credit for saving me. I might

not be here, if not for her. She, too, had lost a spouse in a car accident. She

was working for ‘Reader’s Digest’ and we met and fell in love.”

As a child, John Dos Passos was known as ‘John R.

Madison.’ His father, one of New York City’s most important and wealthiest

corporation attorneys was not married to his mother, Lucy Sprigg. He attended

schools inEngland, until the death of his father’s first wife. He would later

return to Virginia and Westmoreland County after the marriage of his mother and

father.

Well read, brilliantly educated, Dos Passos as a young

man graduated from Harvard and went overseas, just as Hemingway had done to

drive ambulances for the ‘Red Cross,’ as the First World War exploded in

Europe. After the war, he cultivated the friendships of poet ‘e.e.cummings,’

critic ‘Edmund Wilson,’ writers ‘F. Scott Fitzgerald, Dorothy Parker, Ernest

Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, James Joyce and Sherwood Anderson.’

Dos Passos lived for a while in London and Paris and

traveled extensively through Europe and Russia after the war.

While still in his twenties, Dos Passos wrote ‘One

Man’s Initiation:1917,’ a novel about the First World War, “Streets of Night,”

the classic “Manhattan Transfer,” and another great novel, “Three Soldiers.”

His play, “The Garbage Man” was performed in New York

and he worked on nonfiction books such as “Rosinante to the Road Again,” taking

his title from Cervante’s “Don Quixote.”

It was during this period that he was arrested for

publically protesting the handling of the ‘Sacco and Vanzetti’ case in Boston.

He later wrote about it. Along with writers, ‘Theodore Dreiser’ ( “Sister

Carrie” and “An American Tragedy”) and ‘Upton Sinclair’ (“The Jungle” and the

‘Lanny Budd ‘ series) Dos Passos protested the treatment of miners in

Appalachia and wrote about that, too, with a distinctly “socialist bent.” It

wasn’t until after the Spanish Civil War, which he covered with Hemingway, and

the assassination of his friend and translator, that Dos Passos’s political

views took a radical swing from the Socialist ( thought never Communist) view

of the left to the conservative right.

During the 1930s, Dos Passos’s books, “1919,” “The Big

Money” and “42nd Parrallel” which make up the trilogy “U.S.A.” were fervently

embraced by the political left in this country. French author Andre Malreaux

called Dos Passos “America’s greatest living writer,” totally ignoring the

achievements of Hemingway, William Faulkner, Thomas Wolfe, John Steinbeck, John

O’Hara and James T. Farrell.

However, with his sudden and extraordinary shift to

the conservative right in the 50s, Dos Passos lost his “critical readership.”

The left wing intellectuals of the thirties turned against him. Dos Passos was

no longer in vogue and his big books of this period–though just as expertly

executed–”Chosen Country,” “The Adventures of A Young Man,” “Number One,”

“District of Columbia,” the trilogy that did for conservatism what “U.S.A.” did

for the Socialist view, all had disappointing sales. It wasn’t until his 1961,

bestseller, “Midcentury,” a novel that captured the flavor of present day

America and used some of the same Newsreel techniques created in “U.S.A.” that

Dos Passos once again found himself on the bestseller lists.

“Midcentury,” though it is not a great novel, in the

same way that “U.S.A” is great, is still a superior work as it examines the

life of the fictional Jay Pignatelli, who is obviously based on Dos Passos

himself. It also takes us inside the lives of popular American heroes such as

Marilyn Monroe, William Randolph Hearst, James Dean, Henry Ford, Franklin

Roosevelt, etc., which means it’s also fun to read.

In later years, Dos Passos also worked on the

non-fiction historical biographies, “The Head and Heart of Thomas Jefferson”

and “Mr. Wilson’s War,” about the First WorldWar. He also wrote his memoir of

Paris, Hemingway, Fitzgerald and ‘the lost generation,’ and called it “The Best

Times,” published in 1966. It is a counterpoint to Hemingway’s own memoir, “A

Movable Feast,” which covers many of the same places and people. (That book is

being reissued next year with material cut from the original edition.)

In the 1930s, Dos Passos wrote the the motion picture,

“The Devil Is a Woman” for Marlene Dietrich. “Dietrich was quite a girl,” Dos

Passos smiled, lighting his second ‘Cubana.’ “I didn’t want to stay in

Hollywood, the way Scott Fitzgerald did. He had hopes of becoming a director

and producer. I didn’t. And, Scott died there of a heart attack, far too early.

Just 44. William Faulkner arrived in Hollywood and went immediately to work for

‘Howard Hawkes.’ He wrote an adaptation of Hemingway’s ‘To Have and Have Not,’

that was very different from the book. Raymond Chandler also worked in the

studio system, which made films of his ‘The Big Sleep’ and ‘Farewell, My

Lovely.’ Faulkner and Chandler both desperately needed the money.”

“There is a story about the legendary ‘Jack Warner,’

who ran Warner Brothers Pictures. He always bragged that he got a Nobel Prize

winner—William Faulkner–for $150 a week, when another writer he had on the

payroll, with none of Faulkner’s abilities or credentials was getting $5,000

per week for working on the same script.”

“Faulkner asked Warner, if he could go home and write

on the script. ‘Sure,’ Warner said–and to his surprise, Faulkner got on the

first plane and flew home to Oxford, Mississippi to finish his screenplay. But,

Warner was not good to writers. Referred to them as ‘smucks with typewriters.’

“

In August 1969, Dos Passos was still writing and

researching his last non-fiction book, “Easter Island,” that was due to be

published by Doubleday the following year. He was also working on another Jay

Pignatelli novel about the character who first appeared in “Chosen Country.”

John Dos Passos died in his Baltimore apartment, his

winter retreat away from his estate in Westmoreland County,Virginia, of a heart

attack in 1970. He was 74 years old.

Author’s Note: A short time

before his death, Dos Passos inscribed a pamphlet about the ‘Space Program’ on

which he had been working for NASA. He spelled the author’s name “Paine,” as in

Tom Paine, one of his favorite characters of the American Revolutionary Period.

Ronald Payne received the news of Dos Passos’s death while sitting in a

Richmond bistro, with his then fiance’, Paula Jones, now Mrs. Danny Meade

of that city.

Payne attended services for ‘John Dos Passos’ in

Westmoreland County,Virginia, with William F. Buckley, Jr., at his side, who

called Dos Passos, “One of those writers for the ages….”

Posted in Dos Passos, E. E. Cummings, Ernest Hemingway, F. Scott

Fitzgerald, One Man's

Initiation, Writer-RONALD

PAYNE | Tags: A Farewell To

Arms, Beloved Infidel, For Whom the

Bell Tolls, Gore Vidal, Hadley

Richardson, In Our Time, John Steinbeck, Martha Gellhorn, Mary Welsh, Tender is the

Night, The Great Gatsby, The Sun Also

Rises, To Have and Have

Not, William F

Buckley Jr, William Faulkner

Comentarios